-

![LANG-CODE-KEY]() LANG_NAME_KEY

LANG_NAME_KEY

Wargaming are funding an expedition to recover 20 Spitfires, believed to have been buried in Burma after World War II. In this blog entry, we take a look at the history of the Spitfire.

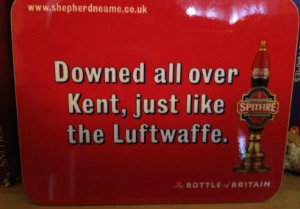

There’s a wonderful scene in the 1969 film Battle of Britain, in which Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring asks one of his Luftwaffe officers what he needs to defeat the RAF, in preparation for Operation Sealion – the invasion of Britain. The officer brazenly replies “Give me a Squadron of Spitfires!” which infuriates Göring. Hitler’s second in command turns on his heel and walks away without saying a word. The scene captures the grudging admiration many German pilots had for this deadly fighter. Squadrons of Spitfires (and Hurricanes, the true workhorses) would shoot down hundreds of Luftwaffe bombers and fighters in the autumn of 1940, thwarting the planned invasion and giving the British time to rearm after the disaster at Dunkirk. As Churchill so memorably put it, “Never in the field of human conflict have so many owed so much to so few.” The plane has an almost iconic status for the British. Even today Spitfires are spoken of in reverential tones. They are lovingly preserved at the Imperial War Museum and the RAF Museum. At Bentley Priory at Stanmore there is even a stained glass window commemorating the Spitfire’s role in winning the Battle of Britain. And perhaps more prosaically, Spitfire beer is “downed all over Britain, just like the Luftwaffe.” The British love the Spitfire.

The Spitfire was designed by Reginald Joseph [RJ] Mitchell of the Supermarine Aviation Works in 1935, in response to the Air Ministry’s pressing need for a fast and durable interceptor fighter. Hitler had just repudiated the Treaty of Versailles and was aggressively rebuilding the German military – including the Luftwaffe. Mitchel and his team at Woolston, in partnership with the Rolls Royce engineers at Derby, took up the call and created a radically advanced piece of engineering and industrial design: the K5054, prototype Spitfire. The naming convention employed by the Air Ministry in the 1930s was to select names that began with the same letter as the plane’s manufacturer. Thus we got the Hawker Hurricane, the Bristol Bleinheim, the Gloster Gladiator and so forth. The Supermarine Spitfire got its name from Sir Robert MacLean, the director of Vickers-Armstrongs, whose daughter Ann was reportedly "a little spitfire." According to Alfred Price’s The Spitfire Story, the fighter had a wingspan of 37 feet. The fuselage was 29 feet 11 inches long and the plane had a height of 12 feet 8 inches. It was powered by a 990 HP Rolls Royce Merlin engine – which was soon upgraded to a 1,045 HP engine. The fighter could reach speeds of 380 mph and climb to 30,000 feet. It weighed 5,332 lbs. fully loaded. The test pilots found the new plane handled remarkably well. The plane was fast and highly manoeuvrable. It could make tight turns at high speed. Owing to production difficulties, the first Spitfires were not delivered to the RAF until July 1938, as storm clouds were gathering over Europe.

|

|

| Reginald Joseph Mitchell | Spitfire beer |

The Spitfire would ultimately see service in all theatres of the war. The plane was designed as an interceptor fighter to shoot down the Luftwaffe’s bombers, but in practice it was used to take on the BF 109 escort fighters, while the less nimble Hurricane fighters took out the bombers. After the Battle of Britain, Spitfire Mark Vs helped turn the tide in North Africa, driving back Rommel’s forces after El Alamein – and ultimately helped soften up defences for the Allied landings in Sicily and Italy in 1943. Spitfires later took part in the Normandy campaign and – from bases in France – pounded the Luftwaffe into submission 1944 and 1945. The Spitfire even saw service in Russia. In response to urgent requests from Stalin, Churchill shipped hundreds of older model Spitfires through Iran to Russia in 1942. They helped turn the tide until replaced by the new Yak-1 fighter in 1943. In the Far East, Spitfires came late to the fight, deliveries of this potent aircraft being prioritized for other theaters of war. However, in Burma, the newly equipped Spitfire squadrons helped thwart the Ha-go Japanese offensive in 1944 and ensure air superiority for the re-conquest of Burma in 1945.

The Spitfires of our quest – according to David – had been shipped in transport crates from the UK to Calcutta, and from there on to Rangoon, in preparation for Operation Zipper, the campaign to capture Malaysia and ultimately Singapore. The planes – reportedly Spitfire Mark XIVs – would have either been reassembled in Calcutta (possibly at Baigachi airfield) and then flown in to RAF fields in Burma or – once the port was reopened - shipped directly to Rangoon, loaded on a special trailer the troops called “the Queen Mary”, and driven by lorry to Mingaladon airfield. The dropping of the Atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 ended the war before Operation Zipper got under way. What happened to the planes is lost to history. The aircraft were never struck off record. They might have been sold to India, the French in Indo China, or the Dutch in the East Indies. They may even have been transported or flown to other RAF bases. But witnesses stationed at Mingaladon at the time reported seeing or hearing about crates “the size of a double decker bus” being buried at the end of the runway, near the turn-about. The documentary evidence that has survived is up until now inconclusive.

Why the planes were buried (if indeed they were) is a mystery. David suggested they may have been buried to support the Karen (Kayin) people of Southern Burma, staunch allies of the British during the war, in the event that a communist led government took control in post-Colonial Burma. The KNU (Karen National Union) would ultimately rise up against the central government in 1949, soon after independence. They were defeated. Another theory is that it was a simple disposal job – too much war material at the airfield, not enough personnel to deal with the backlog. Once the war ended, there was not a whole lot of need for an interceptor fighter, for the simple reason that there were no enemy fighters to intercept. There were however a quarter million Allied soldiers still in country who needed to come home. And there thousands of British POWs, many of them grievously mistreated by the Japanese – such as those who worked on the infamous Burma Railway, immortalized in the Bridge Over the River Kwai. What were needed were Dakota transports, to bring food to starving people, and to bring the boys home. Spitfires – crated or not – were in the way.