-

![LANG-CODE-KEY]() LANG_NAME_KEY

LANG_NAME_KEY

The War in the Pacific began on December 7, 1941 with the Japanese bombing of the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbour. Four American battleships were sunk and four damaged. Six of the battleships (all except USS Oklahoma and USS Arizona) were later returned to service, two after being refloated. The all-important American carriers were out to sea and escaped the attack. The next day, on December 8, the Japanese XV army invaded Thailand and the XXVth army landed in British Malaysia, advancing down the Malay Peninsula towards Singapore, which fell on February 15th. “Fortress Singapore” was the lynch pin of Britain’s defences in the Far East, so its loss – and the loss of the battleships HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales – presented a grievous blow to Allied plans. With the British and American fleets checked, the Japanese quickly overran the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands in early 1942. The Japanese invaded Burma in January.

|

|

| The USS Oklahoma burning | Escaping from the "HMS Prince of Wales" |

Burma was vital to the British and Allied war effort for several reasons. Firstly, Rangoon was the main port for transporting supplies to keep Chiang Kai Shek’s forces (The Chinese National Army) in the fight. If they lost this life-line, Chinese resistance might very well have collapsed and the Japanese triumphed, freeing up entire armies for operations in other theatres. Moreover, a Japanese conquest of Burma would expose India to invasion. Indeed, by early 1942, the Japanese Imperial Navy was able to range freely in the Eastern Indian Ocean, and even attack British naval bases in Celyon. Both Roosevelt and Churchill recognised the importance of holding Burma. In The Hinge of Fate, Churchill reproduced Roosevelt’s letter to the American delegation for the London conference in July 1942, in which he argued that the Allies must hold the Middle East to prevent the loss of the Suez Canal and thus Germany and Japan joining hands in India. If Auchinleck had failed to halt Rommel at El Alamein, and British and Indian forces defeated on Indian’s eastern border, then this scenario might very well have unfolded – especially in the event of collapse of Russia in late 1942, as seemed possible when Operation Blau steam-rolled over Southern Russia and reached the Caucuses.

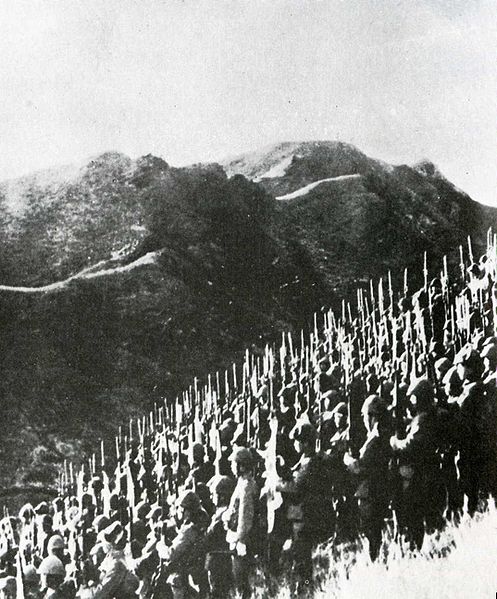

The Japanese Army on border of Burma

The Japanese Army on border of Burma

The forces available to defend Burma in January 1942 were small, scattered, and lacking a coherent command structure. These included elements of the 17th Indian Division, the Burma Rifles, the Burmese Military Police, the Chinese Expeditionary Force, battalions of the British army, and the AVG – American volunteer group, also known as the Flying Tigers. General Hutton was the on-the-ground commander of Allied forces, reporting to General Archibald Wavell, Commander in Chief of ABDA (American British Dutch Australian) forces in South East Asia. According to Louis Allen, author of Burma: The Longest War 1941-45, the defence of Burma rested on the assumption that the Japanese would stage an amphibious assault on Rangoon, seize the capital, and then push in-land with supplies arriving through the port. The Allied Chiefs of Staff were thus surprised when the Japanese invaded from Thailand through the Kwakareik pass. The Japanese quickly captured Moulmein and pushed British forces back to the Sittang River. General Smyth ordered the Sittang bridge blown to prevent its capture – a controversial decision which stranded the 17th Division on the wrong side of the river, and ultimately left British forces too weak to hold the West bank. On March 7th, the British were forced to abandon Rangoon and retreat north to Mandalay to regroup. The Japanese had succeeded in their objective to cut the Burma Road. By early May the Chinese 6th army retreated into Yunnan province and the British withdrew into the Indian State of Assam and Bengal. Allied fortunes in Burma were at low ebb.