-

![LANG-CODE-KEY]() LANG_NAME_KEY

LANG_NAME_KEY

“This is Burma,” Kipling wrote, “and it will be quite unlike any land you know about.” Kipling was right. My many years of traveling to China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea did not prepare me in the least for Myanmar. I was about to learn. When we departed for Myanmar, I naively thought that we would travel to Naypyidaw (the capital) within the week, meet with the Ministers, and finalize the contract – since after all it had been negotiated several months before. I confidently predicted we would start digging before the monsoon rains began to fall. It did not work out that way. Instead, we would spend the next five weeks in Myanmar, navigating the bureaucracy and feeling a bit like Mr. K in Kafka’s novel The Trial (the German title Der Process better captures it). Business does not move quickly in Myanmar. Sometimes it doesn’t move at all.

On June 2nd, the day after our arrival in Yangon, we learned from our Burmese business partners – a mining & construction company called Shwe Taung Por – that the Ministers were confused about the British government’s relationship to the Spitfire project. The confusion arose from Prime Minister David Cameron’s recent visit to Myanmar in April, when he met with President Thein Sein and spoke at length about recovering the Spitfires and repatriating them to Great Britain as a joint heritage project. The Prime Minister had learned about the project from Steve Boultbee Brooks, who had flown over to Yangon to meet Mr. Cameron in Myanmar, a few days after meeting David. Mr. Brooks, a wealthy property developer and owner of the Boultbee Flight Academy, secured a meeting with the Prime Minister in Yangon, with the assistance of the British Embassy staff. At the time, the Prime Minister was facing criticism at home for his Asia trade mission. The Spitfire project offered an uplifting end to his Asian tour: a joint heritage project to bring the UK and Myanmar closer together – he was pressing to lift sanctions – and generate some positive PR for his administration.

The Spitfire story broke in the Telegraph on April 14th with the headline “Spitfires buried in Burma during the War to be returned to the UK.” David was surprised by the article, as he’d been close to finalizing a deal with Myanmar government and did not want any publicity. The newspaper article described David’s 16 year quest to find the planes. At the end of the article, it mentioned that Mr. Brooks was funding the recovery efforts – which had evidently not been agreed. The two men fell out shortly after the article appeared, with David alleging that Brooks had used his access to the Prime Minister to try to take over the whole project and push David to the sidelines. David became gravely ill from the stress. Two weeks later the press got wind of the dispute, and a second article appeared in the Independent on April 28th with the headline “Cameron’s Claim on Spitfire trove ignites British Battle in Burma.” A spokeswoman for 10 Downing Street said that “we hope that this will be an opportunity to work with the reforming Burmese government to uncover, restore and display these fighter planes and have them grace the skies of Britain once again.” To which David, upset with Brooks and the Prime Minister, responded somewhat indelicately “I can do it without Brooks, I can do it without anybody. I’ve been digging up aircraft for 35 years. I don’t need them.” Downing Street was not pleased. Brooks vowed to launch his own recovery team without David – and to get there before the Monsoons. This would be a David versus Goliath battle.

For our contract to move forward, the Myanmar government demanded that we secure a letter from the UK Embassy endorsing David’s proposal to excavate the Spitfires. This was going to prove rather awkward given the recent tiff in the papers. David had embarrassed the Prime Minister. 10 Downing Street was thus disinclined to help. We had a lot of work to do. First we drafted a letter to the President’s office, in which we summarized David’s partnership with Shwe Taung Por and his long quest to find the Spitfires. We requested permission to commence digging on June 20th in Myitkyina – far to the North, where it would still be dry. We specified that the dig would begin at 9:00 AM, as we were advised that was the most auspicious time, in both astrological and numerological terms (I never did learn why). We printed, translated, and notarized the letter, and sent it out on Monday June 4th by courier. Next, we telephoned Second Secretary Fergus Eckersley at the UK Embassy in Myanmar. We explained that we were in Yangon and needed a letter from the British government endorsing the project. Eckersley informed us that the British Ambassador (Andrew Heyn) was very busy. Furthermore, none of the other applicants had requested such a letter, so he would have to discuss it with the Ambassador. This was not looking promising. That evening, we called a friend of David’s friend ( in the UK, who had formerly worked in the Foreign Office. She made some discrete phone calls on our behalf to gather intelligence about our rivals and to convince 10 Downing Street to authorize the UK Embassy in Yangon to write us a letter of support.

Time was running short, our competitors were gaining – we heard rumor that our rivals’ agents were in Yangon – and the Monsoons were coming. We decided to camp out on the doorstep of the imposing stone edifice of the British Embassy in Yangon on June 5th. Unfortunately, Fergus and the Ambassador were out. The guard helpfully informed us that they might be at the Strand Hotel or the British Club. We checked the Strand next door – a delightful colonial era building with white walls trimmed with teak and polished marble floors, islands of wicker furniture and wooden ceiling fans spinning lazily overhead. There’s also a whimsical lost and found with a dusty pocket watch and a lady’s fan that clearly date back to the colonial era. The Ambassador and Fergus were not to be found. In the afternoon, we phoned up Fergus again, explained our predicament, and asked if we could get together to meet. Fergus agreed and graciously invited us to the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, which would be held that evening at the British Club. We made plans to attend.

The British Club is a member’s only club frequented by diplomats and expat Brits. It is surrounded by a wall of white masonry and has a stout wooden gate with a guard house. A Union Jack with an image of the Queen, encircled by the words ‘To Commemorate the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee’, announced that we were in the right place. We found Fergus and the Ambassador on the back lawn, talking with guests. They welcomed us and we chatted about the project over beers. Fergus proved to be an extremely personable and charming fellow. He is fresh out of Oxford. This is his first posting in the Foreign Service. We have clearly put him in a difficult position as he is under injunction to treat all parties equally, despite David’s claim to precedence and the fact that Mr. Brooks had neither been to Burma prior to his visit in April, nor done the research to find the planes.

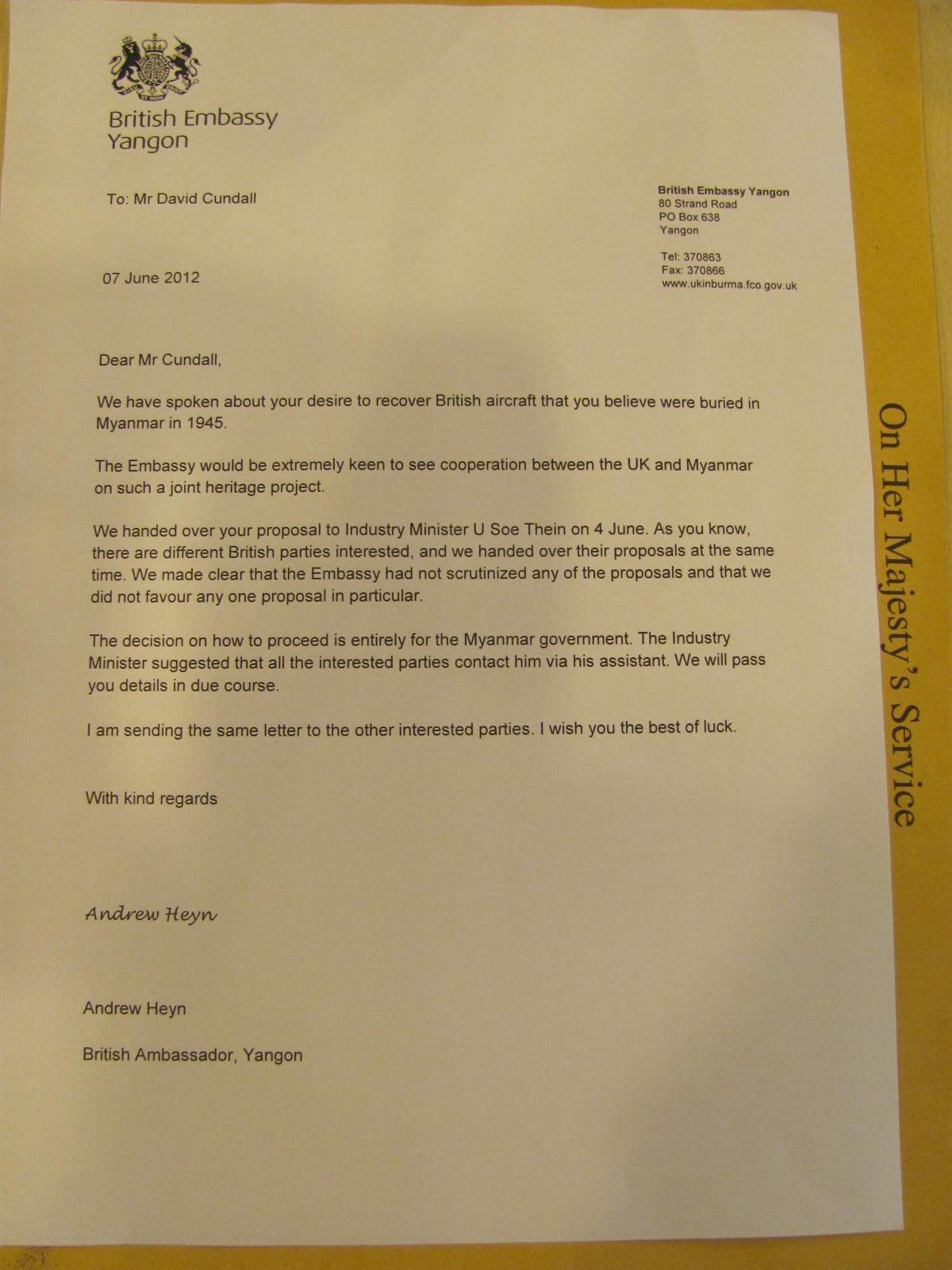

Fergus told us again that the Embassy could not endorse any particular party nor involve itself in commercial projects. I asked if the Embassy would be willing to endorse the idea of recovering and repatriating the Spitfires, without specifically endorsing David’s application over the others. He replied that this would be acceptable, provided we agreed to allow the Embassy to offer such a letter to each of the other applicants. We accepted this proposal, and on Thursday morning, June 7th, we picked up a large manila envelope stamped “On Her Majesty’s Service” from the Ambassador at the Embassy. We opened the envelope and read the letter in the lobby of the Strand Hotel. The letter read in part “the Embassy would be extremely keen to see cooperation between the UK and Myanmar on such a joint heritage project” but “the decision on how to proceed is entirely for the Myanmar government.” It was not the strongest letter of support, but at least we’d got one. We hoped it would be enough.