-

![LANG-CODE-KEY]() LANG_NAME_KEY

LANG_NAME_KEY

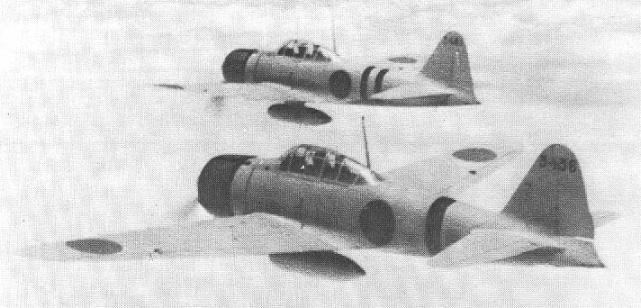

On June 4, 1942, after a raid on Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands, Flying Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga was in trouble. He and his wingmen, Chief Petty Officer Makoto Endo and Petty Officer Tsuguo Shikada, had just shot down an American PBY Catalina, then strafed the survivors in the water. In the process, however, his plane was hit by small-arms fire, which severed the return oil line and slowly starved the engine of Koga’s A6M2 Zero fighter of lubricant.

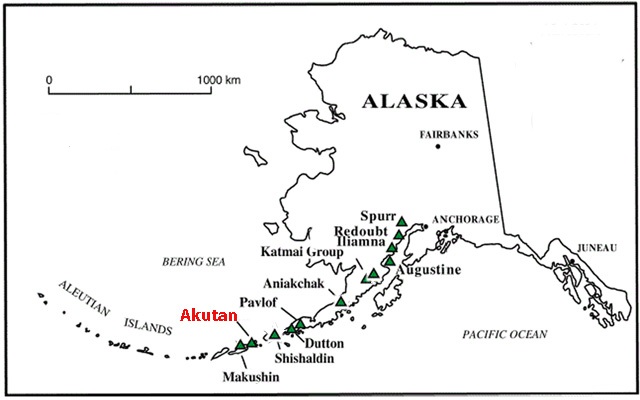

Streaming smoke, Koga throttled back and made for Akutan, an island 25 miles to the east. This was designated as the emergency landing site for the raid; a submarine lay in wait off shore to retrieve downed pilots.

Koga surveyed the island and found a broad, flat, grassy plain a half-mile inland. He dropped his landing gear and prepared to set the Zero down. At the last moment, his wingman saw a glint of moisture reflected from the grass – this was not a grassy plain but a marsh.

It was too late. Koga’s Zero touched down, and the main gear dug into the sodden earth, snapping the plane over onto its back slamming it into the grass with a splash. The two other pilots were under orders to destroy any downed Zeros, but they could not bring themselves to strafe the plane, thinking that, perhaps, Koga was alive but trapped. In reality, Koga was dead, his neck snapped by the violent crash.

The wreck was left behind, and sat untouched until June 10, 1942, when a wayward PBY pilot stumbled across it during a patrol. A team was sent to the site and they discovered the plane to be in good condition; Koga was given a burial, and the Zero was loaded on a barge on June 15. The allies now had a flyable example of the Zero – the first flyable example to be examined by the United States military.

Then, if you believe the myth, the evaluation of Koga’s Zero led to the F6F Hellcat, the mighty Grumman fighter that would vanquish the A6M and every other Japanese plane. The lessons learned from flying the Zero in the U.S. were applied to polish the F6F into a war winner.

That’s a great story. Unfortunately, it’s completely wrong – and yet it continues to be repeated in books and magazine articles about the Hellcat.

In reality, the Hellcat had been in the works for more than a year before Koga’s crash. Grumman was looking to build a superior version of the F4F Wildcat using a more powerful engine – initially, the Wright R-2600, but soon the superior Pratt & Whitney R-2800. The size of that engine meant that the entire plane had to be larger; the landing gear moved from the fuselage to the lower wings to provide clearance for the larger propeller; visibility for the pilot was greatly improved; and the plane had far greater range. In all, it was a very different airplane from the Wildcat even when it was first ordered – on June 30, 1941, a full six months before the start of the Pacific War and a year before the recovery of Koga’s Zero.

In fact, the first flight of a production version of the Hellcat came on October 1942, only two weeks after Koga’s Zero found its way back to the U.S. and began flight testing. This was hardly an opportunity to redesign the Hellcat – rather, it provided an opportunity to hone the tactics of pilots still fighting the Zero in the F4F. It wasn’t until August 1943 that the Hellcat would reach combat, a period in which the Wildcat played a key role – and in which the recovery of Koga’s Zero led to the preservation of many American pilots’ lives.

The Hellcat was a great design for a war of attrition – it could be produced quickly and it was a forgiving plane for new aviators learning the business of carrier air combat. But it was not the product of analysis of the captured Zero – it was the product of the ingenuity of the design team at Grumman. The perpetuation of the myth of the Akutan Zero is an affront to their genius and to the brilliance of the Hellcat on its own terms.