-

![LANG-CODE-KEY]() LANG_NAME_KEY

LANG_NAME_KEY

Pilots,

In this two part historical spotlight, we’re going to take a look at one of the most maligned and misunderstood aircraft of the Second World War; the Bell P-39 Airacobra. After a troubled development cycle and rough career start, the P-39 gained a stigma that’s lasted for nearly 70 years. It was, and still is, regarded as being an underpowered, overweight, and even downright dangerous aircraft to operate, owing to its rather unique mid-engine configuration. We’re going to explore the origins of the P-39s negative reputation and clarify the misconceptions that surround the aircraft. In the first installment, we’re going to take a look at the development and evolution of the P-39 as well as technical specifications of the major subtypes of the aircraft to see service.

During much of the inter-war era, bombers became a central focus of aerial warfare. There was a popular theory developed by Guillo Douhet (and perpetuated among the great Air Forces of the era) that wars would be fought and won by large formations of bombers, prowling the skies with impunity. They would be fast enough to avoid most anti-aircraft defenses as well as the defending fighters. These bomber fleets would then rain bombs down on the civilian population centers. The result of this would be the civilians would be so demoralized that that the government of the afflicted nation would have no choice to surrender. This possibility terrified the governments of the era and considerable interest was put in interceptor aircraft to counter the threat posed by enemy aircraft.

To counter the perceived bomber threat, the United States Army Air Corps put forth Circular Proposal X-609, one of several proposals for a bomber destroying aircraft. This outlined the need for a single engine aircraft which both possessed speed, high altitude performance, and considerable firepower. The aircraft needed to attain a top speed of 400 miles per hour, carry a thousand pounds of weapons (preferably including a cannon), and climb to an altitude of 20,000 feet in six minutes. For 1937, this was an impressive requirement. (For reference, the USAAC’s P-35, which was introduced in 1937, had a maximum speed of only 310 miles per hour).

XP-39

Bell Aircraft Corporation was the first to answer the call with the Model 11, or XP-39 making its first flight the following year. In terms of 1930s aircraft design, the XP-39 was truly a unique aircraft. In direct contradiction to every previous convention in aircraft design, the XP-39 featured a tricycle landing gear (a first for any fighter), center mounted Allison V-1710 engine, and a turbo-supercharger which protruded out of the left side of the aircraft. The reason behind the rather unique placement of the aircraft’s engine was that testing revealed that maneuverability would be considerably increased with an engine placed at the center of gravity. It also allowed for the placement of a heavy cannon armament in the nose.

Performance on XP-39 was very promising. During initial testing the aircraft reached speeds just under the required 400 miles per hour and reached 20,000 feet in five minutes, a full minute under the requirement. The Army Air Corps was very pleased with the performance of the prototype and requested further flight testing. The plane went through a series of design changes, with the new prototype being designated XP-39B. The biggest change to the ‘B’ prototype was the deletion of the turbo-supercharger to improve drag performance.

Unfortunately for Bell Aircraft, the revised XP-39B didn’t have nearly the same performance as the earlier prototype. Instead of the earlier 390 miles per hour, the aircraft instead reached a top speed of 375 miles per hour. More troubling for Bell, and the XP-39, the aircraft hadn’t even been fitted with its armament or its armor. Furthermore, the deletion of the turbo-supercharger also led to heavily diminished performance about 17,000 feet. Whatever promise the XP-39 had originally shown was rapidly dwindling. Attempts to improve the top speed of XP-39 continued into 1940, with both the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and the US Army Bureau of Aeronautics attempting to improve the drag qualities of the aircraft.

By September of 1940, the Army ordered a new series of prototype fighters from Bell, the YP-38. These aircraft featured improvements suggested by NACA which further reduced the drag. However, the addition of armament and armor lowered the top speed further to 368 miles per hour. With armament and armor added to the airframe, the aircraft weighed nearly a ton more than the XP-39 that was first tested. Later variants of P-39 would increase the airspeed, however, the 400 mph mark would only ever be exceeded in a dive.

Bell P-39C

Fortunately for Bell, the US Army was still interested in the aircraft. The Army ordered the P-39C as the first operational variant of the Airacobra, with the first aircraft entering service in January of 1941. Despite the troubled development, the P-39 still had a number of things going for it. The aircraft was still very maneuverable and had simply unrivaled firepower. The P-39C, and the YP-39 before it, were both built to carry the monstrous 37mm Automatic Cannon, M4. The M4 was the largest cannon ever fitted to a fighter by the US Army Air Forces in WW2. The 37mm was also complimented by a pair of synchronized .50 caliber and .30 caliber machine guns in the nose. The P-39 had a series of unique controls for the aircraft weapons. There were weapon selection switching allowing the pilot to select either the cannon, synchronized guns, wing mounted guns, or any combination thereof.

There is a legend that persists that the 37mm armed P-39s excelled as tank busters, particularly in Soviet Service, and this seems rather unlikely. Despite sharing a similar caliber to the gun found on the Stuart series of Light Tanks, the Oldsmobile M4 had noticeably inferior performance to the 37mm M3 mounted on tanks. There was a muzzle velocity difference of about 200 meters per second. The higher velocity M3 was already hard pressed to penetrate the armor on later models of German tanks. It doesn’t seem likely that the lower velocity gun on the P-39 would be particularly effective against tanks unless a hit was scored against the top of the engine deck or perhaps through the top of the turret.

Flying the P-39 for the first time had to be an interesting experience for most of its pilots. Unique for any fighter of WW2, the pilot entered the aircraft through either one of two doors located on either side of the cockpit. At first glance, this would appear to make bailing out of the aircraft difficult since the unfortunate pilot would be forced to open the door into a 300 mph headwind. Bell was quite aware of this, and there was a lever next to each door that would release the pins holding either door in place. They would either fall away themselves or with some assistance from the pilot. The pilot could then roll out of the cockpit and away from the aircraft.

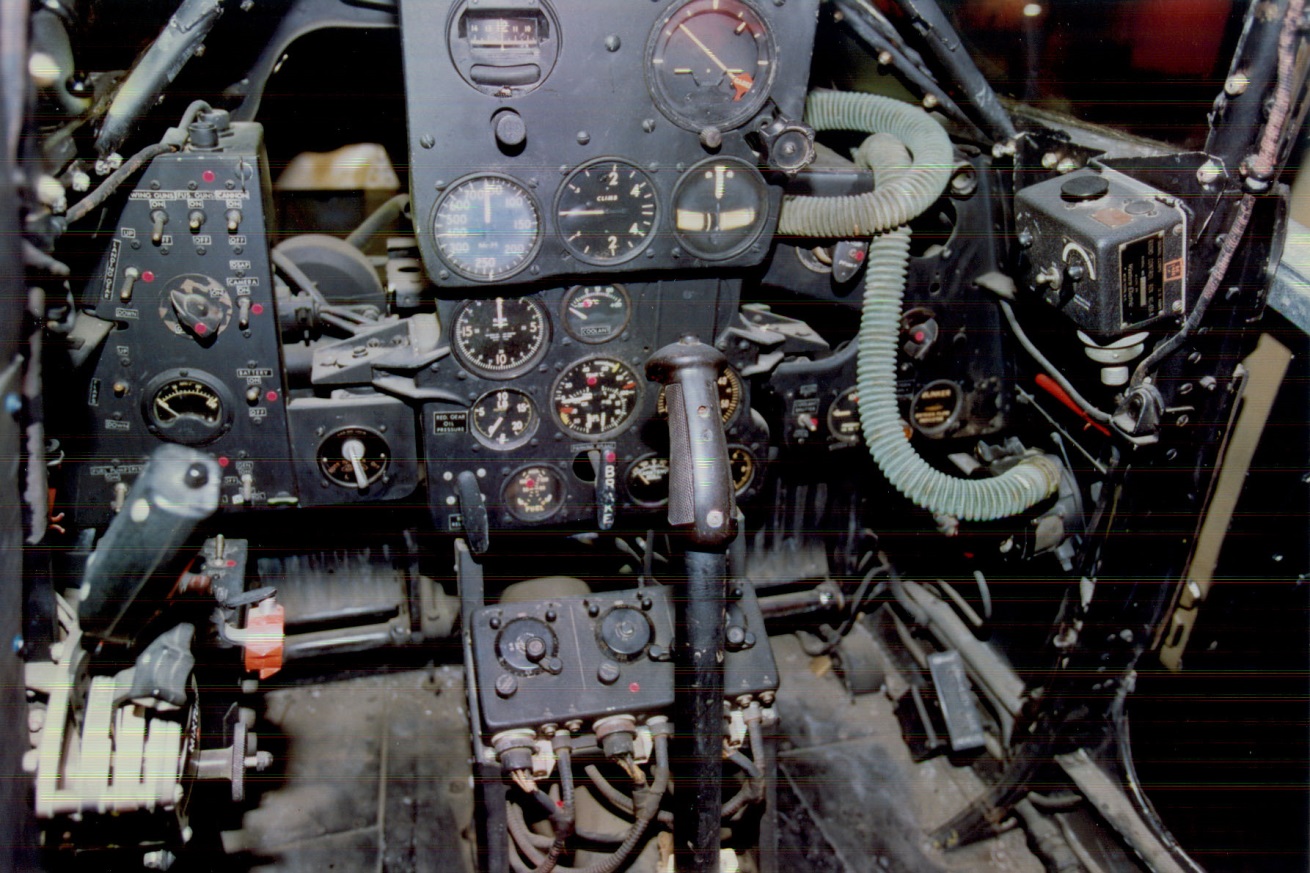

Cockpit of P-39Q

The cockpit its self was well laid out. Despite its unconventional entry procedure, the aircraft did essentially have a bubble canopy. Compared to almost every other US Army fighter in service by 1940 (and indeed that of most other nations), the P-39 had simply unrivaled rearward visibility. The pilot’s view rearward was only partially obscured by radio equipment and the air intake for the engine, otherwise the pilot could almost see directly behind themselves. Only the P-38, and bubble canopied P-51s and P-47s would have the same level of rearward visibility in USAAF service. Also, on a very unique note, the pilot of the P-39 also had access to a funnel shaped relief tube if he felt the need to empty his bladder while flying.

In terms of flight characteristics, the P-39 was by most accounts actually a very pleasant aircraft to fly. P-39 variants were used extensively as trainers in the USAAF. However, it was certainly hampered by a relatively low airspeed. Most variants of P-39 could only achieve a maximum of 368 miles per hour in level flight. Despite its weight, the P-39 was also considered to be reasonably maneuverable and light on the controls. The aircraft also had decent stall characteristics. Stall speed was around 109 miles per hour and the aircraft could be quickly recovered at 145 miles per hour. Ground handling, particularly taxiing was superb. The pilots of nearly every other fighter (save for the P-38) were forced to zig-zag their aircraft left and right down the taxiway in order to see over the nose. With a tricycle landing gear, the pilot in a P-39 could clearly see over the nose.

The P-39 did have a bad reputation for having some nasty spin characteristics. There was a persistent rumor that, when entering a stall or a spin, the aircraft would enter an uncontrollable tumble from which the pilot could not recover. This reputation still exists in some capacity today. At the time, word of it was widespread enough in the USAAF that it warranted some testing. From August 1-3, 1943 a P-39 was put through an extensive series of tests attempting to recreate this legendary tumble. After about a thousand spins, USAAF test pilots were unable to recreate this mythical tumble. The Army concluded that the P-39 had normal spin characteristics for a pursuit aircraft and recovery from a spin could be achieved in two and a half rotations provided the proper recovery characteristics. Additionally, the ‘tumble’ likely a misinterpretation of the inverted spinning and snap rolls of an improper spin recovery.

Bell Airacobra Mk. I of No. 601 Squadron, Royal Air Force

The first P-39 Airacobras to actually enter the war saw action with the Royal Air Force as the Airacobra I. These aircraft, designed specifically for export featured an underpowered Allison V-1710-35 churning out a 1,150 horsepower. Also the aircraft used a Hispano Suiza 20mm instead of the 37mm M4. Armament was upped from the P-39C. The nose .30 calibers were exchanged for a quartet of .303 machine guns in the wings. The .50 caliber machine guns in the nose still remained. Airacobra Is entered service with No. 601 Squadron in August of 1941 and were almost immediately withdrawn from service. 601 Squadron’s Airacobra saw action in all of four sorties over France. The RAF derided the aircraft’s anemic performance over 12,000 feet, low airspeed of 355 miles per hour and short range. The Airacobra I was withdrawn in March of 1942. The remaining airframes were either given to the Soviet Union or back to the USAAF where they were designated as the P-400. The secondary armament was switched out once again for the .30 calibers that were standard in USAAF service.

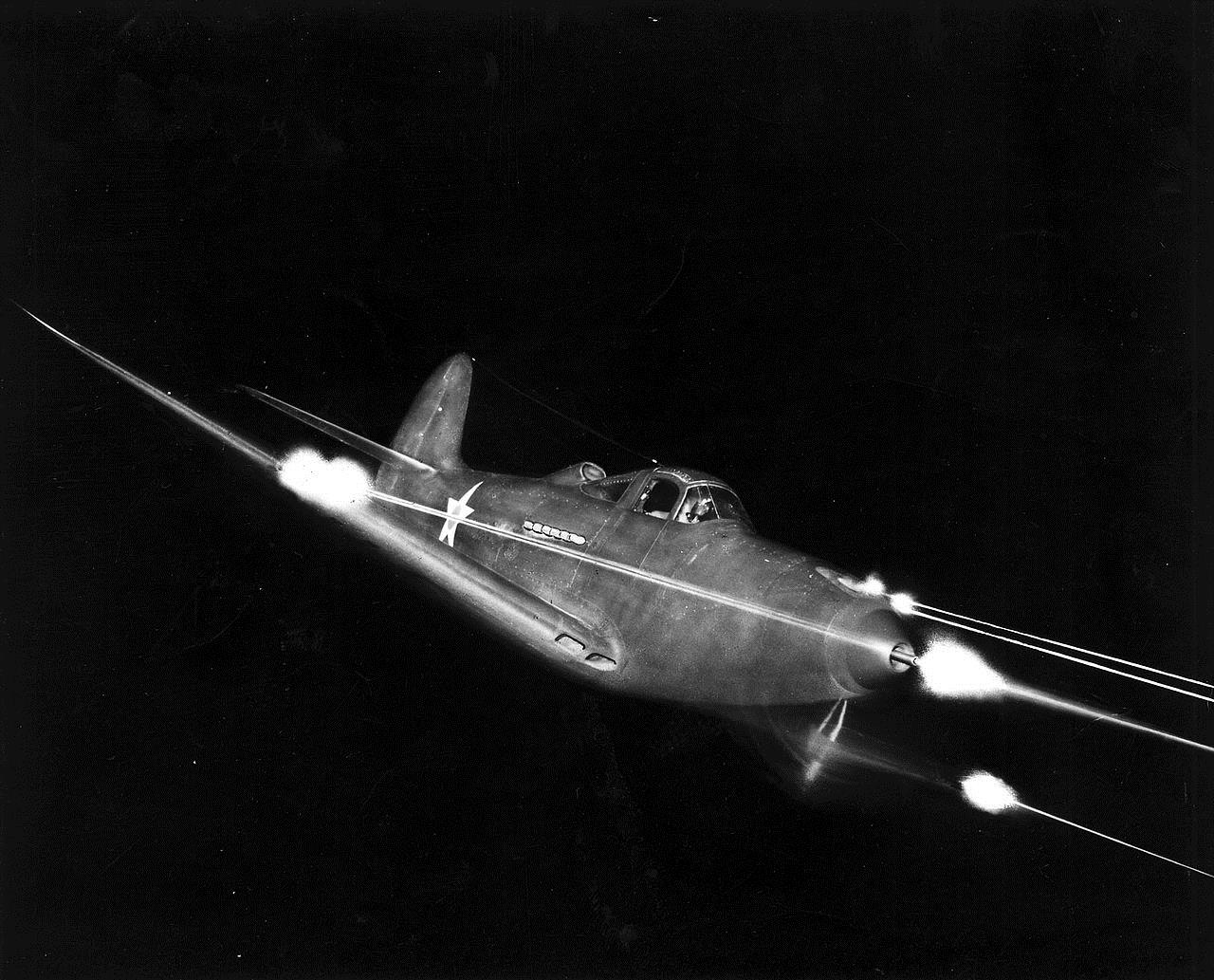

Bell Publicity Photo of a P-39D gun test on the ground. The photo has been manipulated to make it appear in flight.

While the remaining handful of P-400s were given back from the RAF, the first variant to enter service with the USAAF in significant numbers was the P-39D, which entered service in April of 1941. It was the first variant of the Airacobra to enter service in significant numbers and indeed the P-39D establishes the configuration on which the vast majority of P-39s were based. Reception towards the P-39 in American service was certainly mixed. Once again, the aircraft was perceived to be overweight, with short range and lackluster performance about 17,000 feet. Although the US Airacobras were slightly faster than the Airacobra Mk I that was supplied to the RAF. The P-39D had a top speed of 368 miles per hour. The P-39D came in several production blocks, and armament varied depending on the production block. The P-39D featured the 37mm cannon, while the D-1 and D-2 carried the 20mm cannon. Secondary armament was identical to the P-400s with two .50 caliber machine guns and four .30 caliber machine guns. The D model also added a centerline rack for 550 pounds of external stores. The P-39D-2 also upped the power plant from the 1,150 horsepower Allison to the more powerful V-1710-63 which churned out 1,325 horsepower. 924 P-39Ds of various types were built.

The P-39F, J, K, L, M, and N variants all followed the same basic airframe as the P-39D. Armament also returned to the 37mm M4. The P-39F was almost identical to the P-39D except for a change in propeller manufacturer (an Aeroproducts prop was used over the original Curtiss-Electric). The 1,150 Horsepower V-1710-35 from the D and D-1 was used on the ‘F’. The ‘J’ was nearly identical to the P-39F, the only different being a different engine, the 1,100 horsepower V-1710-59 which added an automatic boost feature.

USAAF P-39N

The subsequent variants; ‘K’ through ‘N’ were all initially ordered as the P-39G. This designation wound up not being used, and the would-be G series was divided up and given designations K-N. The P-39K carried the same 1,325 Horsepower Allison that was used on the P-39D-2. The P-39L was almost exactly the same as a P-39K. The model returned to the original Curtiss Electric propeller that was used on the P-39D and had a larger nose wheel. The ‘M’ was an attempt to improve altitude performance with an Allison V-1710-83 which increased airspeed at 15,000 feet to 370 miles per hour. This however, would be further improved by the P-39N. The P-39N brought the weight down from 8,400 (the weight of the K-M models) down to 8,200 pounds. The P-39N was the second most mass produced Airacobra variant with 2,095 aircraft being built. Airspeed was increased to 379 miles per hour with the lighter weight and the addition of the Allison V-1710-85.

VVS P-39Q; The Soviet Union was the largest operator of the P-39Q (note: wing mounted gun pods have been removed)

The most numerous of the P-39 series as well as its final iteration was the P-39Q (4,905 out of a total of 9,584 airframes).The Q also saw the widest array of changes from the configuration started by the P-39D. This aircraft reverted fully to the 37mm cannon, and exchanged the four .30 caliber machine guns for a second pair of .50 calibers in removable gun pods. The .30 calibers lacked the range and power to deal with the heavier armored aircraft that emerged as the war continued. The P-39Q retained the same power plant as the N, but armament change as well as minor improvements to the airframe brought speed up to 385 miles per hour. There were a myriad of P-39Q subtypes, namely differing in use of a four bladed propeller or the more traditional three bladed propeller. Other subtypes had slightly different fuel tank configurations or provisions for Photo-Reconnaissance cameras.

That’s it for the brief development history of the Bell P-39. Hopefully it’s now apparent that the Bell Airacobra had a myriad of capabilities that actually made it a pretty decent aircraft. It was easy to fly, maneuverable, and exceptionally well-armed. Of course, the decision to delete the turbo-supercharger made early in the aircraft’s development condemned the aircraft to altitude service. It will be important to keep the Airacobra’s capabilities and limitations in mind next time when we review the Combat Career of the P-39 in the hands of both the Soviet Union and United States Army Air Forces.